Modern ethnographic research has its origins in cultural anthropology.

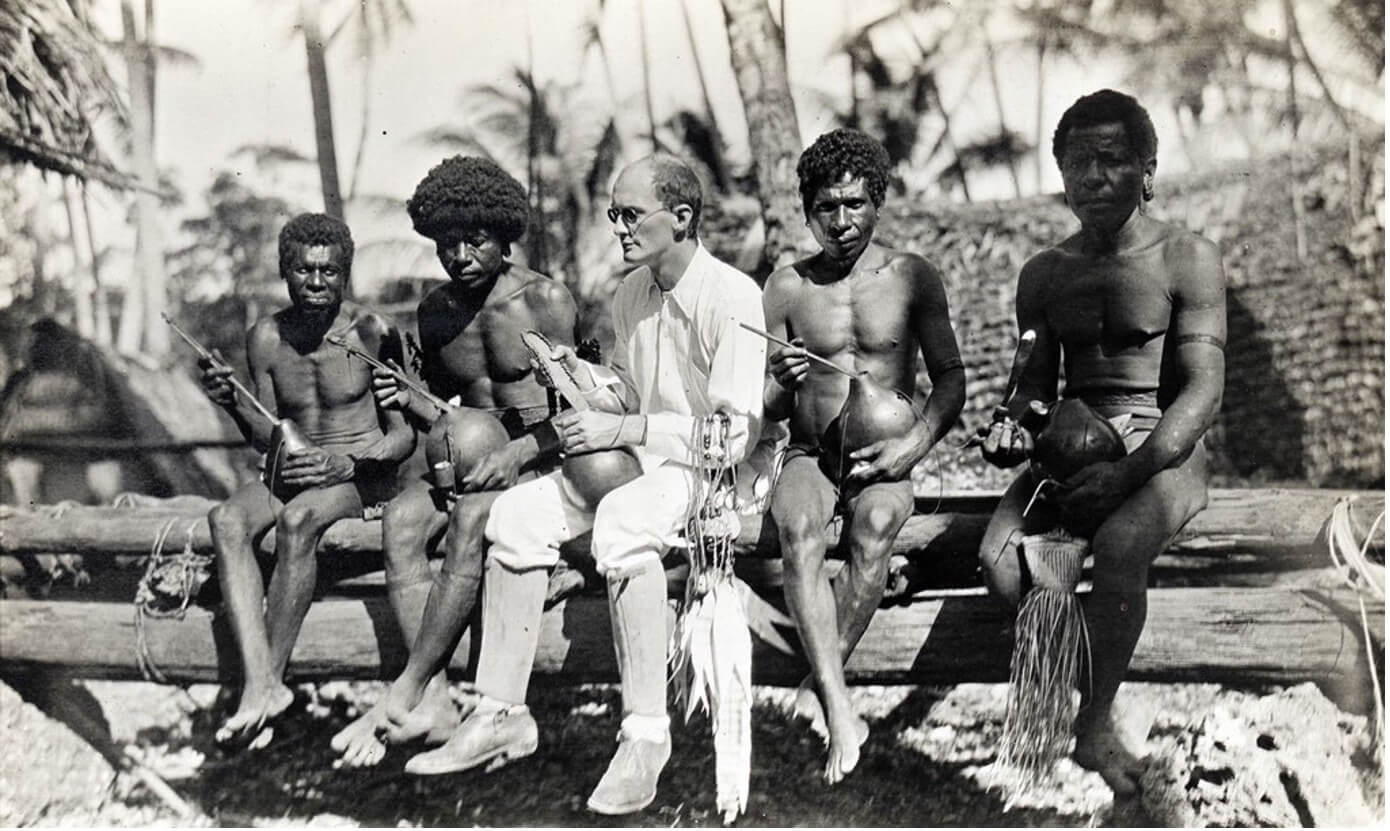

The Polish anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski convinced that it was impossible to know foreign cultures without direct contact with them, conducted the first-ever ethnographic research.

Malinowski spent almost two years on the Triobrand Islands conducting long-term observation of the community living there and participating in its ceremonies and rituals. This was an innovative approach for the time (1918), as earlier anthropology had been dominated by cabinet research or document analysis. Since then, ethnography has become firmly established in anthropology and beyond. How can we use ethnography today, in the design process? How do the methods of cultural anthropology and design complement each other?

Ethnography today

Ethnographic research has applications in social, marketing, or market research. Ethnography is used by companies developing new products or new iterations of existing products: from kitchen appliances or household chemicals to fertilisers for plants, to sophisticated machinery or equipment used in specialised businesses.

Observation of product use or interviews conducted in the consumer’s natural environment yields countless insights into all aspects of the product, such as packaging, visual communication, convenient dispenser, or handle. It is the natural surroundings and the true context of the user that are key in ethnography, making the methods used over a century ago for cultural research, great for designing digital product experiences (User Experience) or digital workplace tools today.

What do ethnographic research and UX design have in common?

Here, the starting point is User Centred Design, in other words, user-centred design.

The term User-Centred Design has its origins in the late 1970s. It was then used by human-computer interaction researcher Rob Kling in his book The Organisational Context of User-Centered Software Designs. Later, the term was adapted and popularised by the American researcher Donald Norman (the same person who, together with Jakob Nielsen, created the Nielsen Norman Group, which is well-known in the UX world).

At the heart of User-Centred Design is the assumption that we design for users and by involving them in the design process – they are the focus of our interest. As designers, we are not omniscient: after all, we do not know all the needs or pains of users, we do not live in their context and environment, so we cannot fully imagine the problems or challenges they face. At the same time, we want to design digital products that effectively solve their problems and address their needs. This is why User-Centred Design involves research with users at every stage in the digital product design cycle.

The observation technique is essential to get to know the user well, their behaviour, context, constraints as well as expectations. Likewise, the other techniques used in ethnography, through which we are closer to the user. By listening carefully to the user, we are able to design digital products that solve the real problems of the product’s recipient and address their actual – often not obvious at first glance, or even unexpressed – needs. Otherwise, we risk investing in a system that responds to the needs imagined by the designers rather than the real needs of the product’s audience.

Ethnographic research techniques: observation, contextual interviewing

Ethnographic research usually uses observation and contextual interview techniques.

As a rule, these techniques are intertwined: the data obtained from the observation is complemented by the information obtained from the contextual interview, and vice versa. We often find that the interview part adds a great deal: it makes it easier for us to interpret what we have observed.

Remember, however, that ethnography does not always have to be ‘pure’ ethnography. Elements of ethnography can be part of other research e.g.: observation during field interviews or ‘autoethnography’ used in diary methods.

Would you like to know more about UX research?

The value of participatory observation

You may have heard of two types of observation: participatory and non-participatory. Non-participatory observation is when the researcher is not part of the group under study, does not interfere in the course of events or processes, tries to stay on the sidelines of the events being observed, and does not influence the structure of the group. Participatory observation means that the researcher becomes a full-fledged member of the community or group in question, immersing himself in its everyday life and empathising with the situation of the subjects. In practice, however, almost any observation in research related to digital products will be ‘participatory’ to some degree.

Being with and around the user will bring you enormous value.

You will get to know the whole context of the user, you will not only focus on the interface, but also on all the factors around. You will get to know the user’s real problems, needs, and pains. You will see how he reacts to the system or service when confronted with certain problems or tasks. You will observe directly his behaviour and emotional reactions, you will see where the system does not meet their needs. You will notice the workarounds, and the detours the user uses to get around the inconveniences the system is serving up.

You will discover when a system, even one that seems well designed, is completely unsuited to the user’s realities. You will observe what external stimuli reach the user and what difficulties they have in using the device, such as the noise level in the working environment, the intensity of the light, or the total number of screens and electronic devices around.

Ethnographic research in the design process of digital products

Let’s return to design. How, then, does ethnographic research fit into the digital product design process? When to introduce ethnography and how to use the mentioned techniques taken from cultural anthropology research?

You can conduct ethnographic research at virtually any point in the product development cycle.

They are applicable when you are just looking for an idea for a digital product. You feel that there are challenges or problems in a particular audience that could be solved digitally, but you still have too little knowledge about that audience and its problems.

You can use ethnographic research when a digital product already exists, but you know it will need to be redesigned because it doesn’t meet your audience’s needs fully or doesn’t address the needs of all target subgroups.

Ethnographic research will also be a great choice when you know that your users are interacting with an entire ecosystem of services, systems, or devices that are not working effectively. Such an example is often the work environment, where employees often use many different types of systems, platforms, services, and applications that together form the so-called digital workplace.

Before you start redesigning this ecosystem or decide to replace several systems with one that catches all needs, you should immerse yourself in the world of users.

Ethnography can be applied at different points in the product development cycle and allows you to answer a number of different research and design objectives and problems. It is qualitative and exploratory in nature, so it will help you both identify problems and seek solutions, and gather valuable inspiration for further product development.

The role of ethnography in optimising the digital workplace

Digital workplace research is an essential part of the projects we carry out. The digital workplace is made up of a whole ecosystem of systems, tools, and devices and, of course, people often scattered around the world in different locations and working in different cultural contexts.

We have clients coming to us, including large multinational corporations, who want to improve this digital working environment [digital workplace]. They perceive that in their organisations, communication, and collaboration based on legacy tools are neither sufficiently effective nor satisfying for employees. As part of the wider digital transformation of their companies, they are looking for opportunities for improvement and optimisation. It is important to them that digital transformation takes into account key developments and phenomena of recent years, for example, the spread of remote working.

In a further step, clients want to define what this optimisation should consist of. Should the tools used in the locations be made more consistent? Which tools should be recommended? Or perhaps a reduction in the number of tools? How about replacing several different systems with one global one? This is where the work of cultural anthropology and ethnographic research comes to the rescue.

One incredibly interesting digital workplace project we had the opportunity to undertake was a global project for an FMCG corporation. Ethnographic research and observation of the non-digital context brought us a wealth of insights that we would never have come across had it not been for ethnography and the visits of several researchers to different locations around the world.

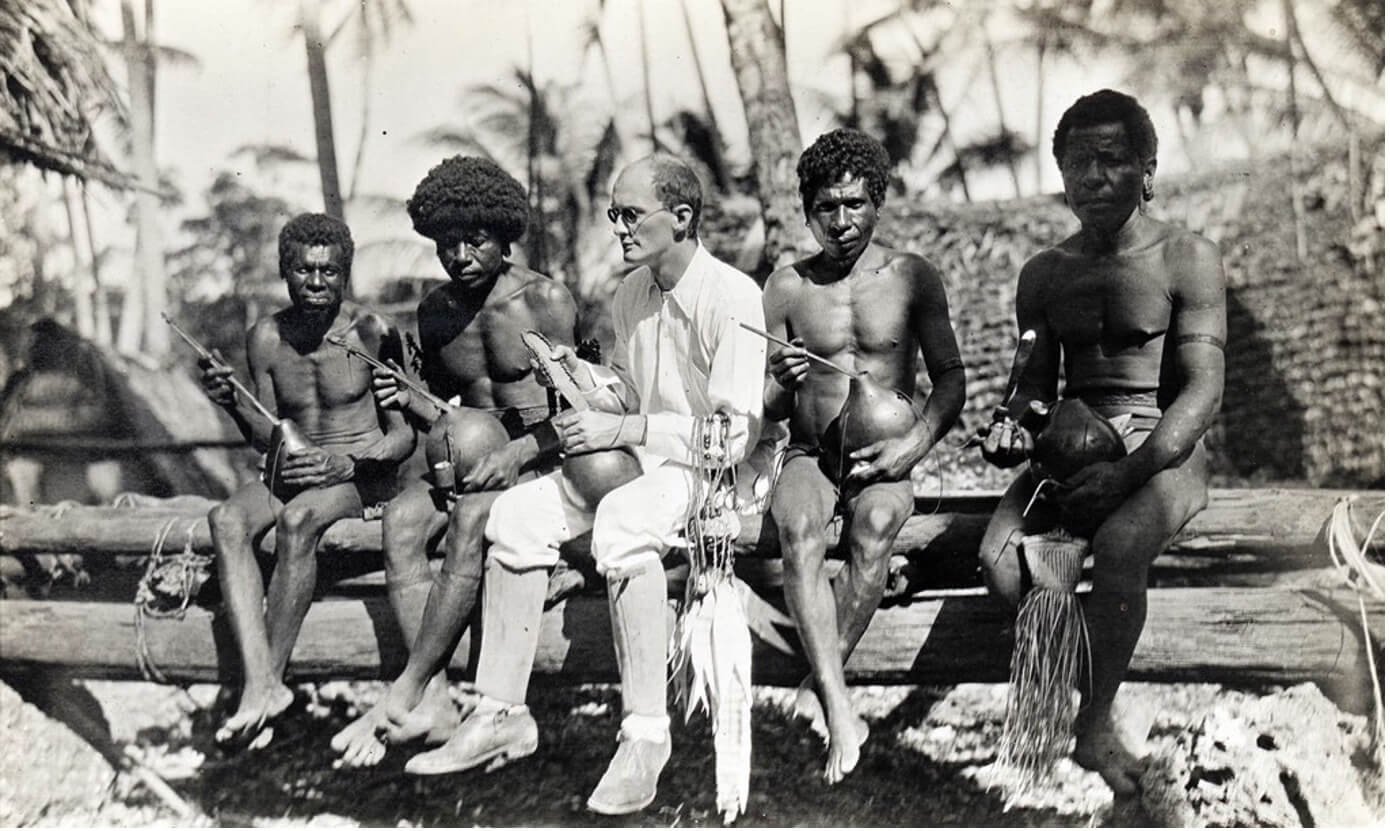

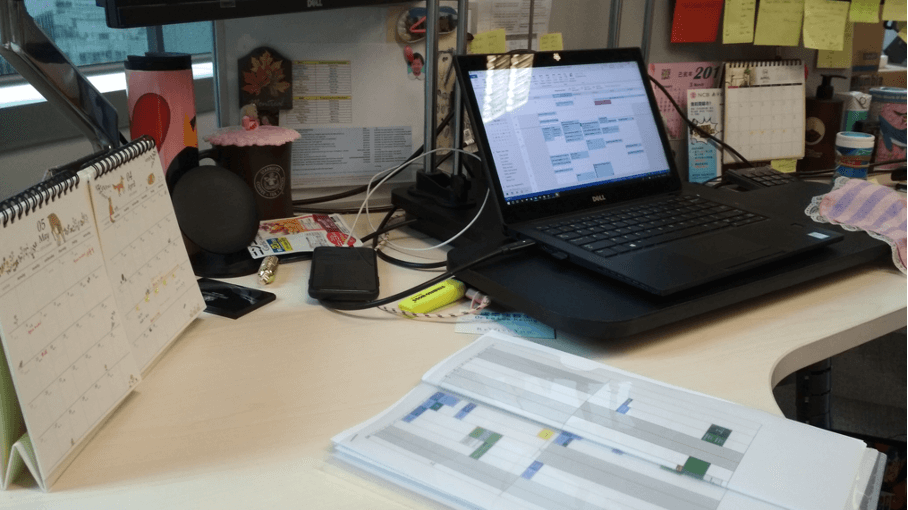

An example? One of the tools analysed was a calendar. In the picture below, the user has three calendars on his desk in addition to the web calendar, plus a printed financial plan for the whole year. What was the user’s perspective? He explained that he needed some dates and deadlines to be ‘out there’.

What might this mean for designers? In the company’s digital systems and tools, either this information is missing or very deeply hidden.

When carrying out digital workplace research, keep your eyes and ears open for anything that might indicate gaps or inadequacies in digital solutions. You are most likely to find hints in a non-digital context, in the form of notes, printouts circled in colour, post-it notes stuck around or boards full of business cards and flyers.

Even more insights you won’t come across without ethnography

What else can observing a non-digital context bring you? Sometimes, when carrying out ethnographic research, we notice that the digital solutions present on-site do not quite ‘fit’ with reality.

The offices in Hong Kong were indeed very digital, but when the researchers went into the field with the sales representatives, it turned out to look like the picture:

We saw that salespeople often take neither a tablet nor a sales logging device with them because they have a delivery carton and various papers in their hands. The tablet is bulky because he will not put it in his pocket. What is the conclusion from this? Sales reps need either another, smaller device than the tablet, or the ability to carry the tablet hands-free, such as clipping it to their trousers.

You will never come up with many of these insights until you have spent enough time with users in their natural environment and in direct contact with them!

During just an hour-long remote interview outside the context of the activities you are doing, the chance that someone will tell you directly about some inconvenience in using the system is far less than if you spend almost a whole day with that person and are next to them when they are confronted with specific problems.

How to plan and prepare ethnographic research?

Then get to work! How do you go about planning an ethnographic study in a user-centred design process? In your planning, consider the place, the time, the people, and all the necessary materials. Let’s start with the location.

How do you select the locations for the study?

Choose together with your client the locations where you will conduct the research. Consider whether the locations (e.g. outlets, shops) differ in terms of the characteristics relevant to the research.

For example, when we conducted exploratory research for a large drugstore chain, we selected shops located in different city locations, e.g. a very busy drugstore in the very centre of the city, located in a key traffic point in the city, a drugstore in a shopping mall and a drugstore on a housing estate in a peripheral point of the city.

The study involved a task-based intranet with an extensive module for managing the daily tasks of employees in drugstores across Poland. Together with the client, we expected that drugstores in different types of locations would differ in terms of the rhythm of the day, the type and intensity of the tasks that employees have to perform, and thus the way they use the system. It later turned out that this was indeed the case: the intensity of customer traffic and the space determined employee behaviour. In a shopping centre, we saw a fairly large staff room with a cloakroom, a separate computer room, and space for unpacked goods. In a drugstore operating in a town centre building, the rooms were narrow and not all on one level. In locations with different spaces, employees shared tasks differently and a common desktop computer from which they used a task-based intranet. Covering different types of locations in the study was therefore a good lead.

How do you select participants for the study?

If you are conducting ethnographic research to support the design of a new system or the development of an existing one, first established with the client for which target groups the system is/will be designed.

Consider whether these individuals might differ in terms of the characteristics that are relevant from the perspective of the research topic. E.g. the parts of the system used, the range or frequency of tasks performed on the system, the access to the device on which they will use the system, and the context in which they will use it. Or are there other characteristics that could potentially affect how they use the system?

Try to look broadly and plan your research so that you talk to representatives of each of the relevant target groups or subgroups. Ethnography is qualitative research, so the principle will be similar to other qualitative projects: talk to a number of people who form a coherent group in terms of characteristics relevant to the research topic.

For example, when working on the redesign of an intranet for a major manufacturing company, we talked to the client about the diversity of the intranet’s target groups. The client let us know that while he had some knowledge or intuition about the patterns of intranet use in offices, he knew little about how intranet use and the needs of manufacturing plant employees. He was also aware that quite a number of people in the plant do not have access to their assigned laptops and use the shared computer in the common area. We had a lot to discover in this project!

We included the most relevant audience groups in the survey: office workers and production workers. Within each of these groups were people at different job levels (e.g. regular employees, managers, shift supervisors, production process operators, and engineers).

Make sure the customer announces you!

Arrange with the client to announce you – the location staff need to know that you will turn up and can let you in. Remember that they are bound by confidentiality, so in order for them to feel safe to open up to you they need to have confirmation from their superiors that you are a trusted person and are actually working with their company.

If you are conducting field research with a wider consumer group, also ensure that your interviewees have no concerns about who they are talking to. You can ask your client to prepare a badge for you with the brand logo or prepare a letter confirming that the brand is carrying out the research. This is also in your client’s interest – they will certainly want to inspire confidence and present themselves credibly in front of their own clients.

How long should the visit last?

The duration of the visit to your chosen location should be an appropriate length. It is best to spend at least one day at a single location.

If you already have some preliminary information from the client about the rhythm of the day in the organisation, be sure to include it. For example, if you know that in a production plant, the day starts at 6 a.m. with a meeting led by the shift manager, be there at that time. It may happen that you start the day even earlier. This was the case when we did a project for a courier company – the researcher would start the day between 4 and 5 am and spend a full shift with the courier. Remember that the rhythm of the day at observation sites changes and it will be valuable for you to observe both the moments when there is a lot going on and the quieter moments. You can use these quietest moments for interviews.

When you are researching in a public place or, for example, in a shop and you are keen to observe behaviour at a precise moment, such as sending a parcel in a parcel machine or using a self-service checkout, you may find that the best choice is to visit during the busiest times. Ask the client if it has data on traffic volumes by location and schedule visits by the research team at these times.

Research materials

Before you go into the field, you need to prepare and outline a certain range of issues and questions that will interest you during the visit. Keep these steps in mind:

- Write down in bullet points the key areas of issues that interest you and the key questions you want to discover answers to.

2. Don’t treat this list as a fixed and rigid research scenario, but rather as a list of things you are curious about. Observe and listen carefully, always be open to new threads, but never forget the main purpose of the study (e.g. exploration for intranet design), and do not spend time on observations completely unrelated to the topic of the study.

3. List the places you want to visit and observe. E.g. if you will be conducting research in a production plant, you will be interested in the whole installation, i.e. for example the control room, a room shared by a wider group of employees, a staff room, a production hall, or a canteen. If respondents do not take you there, ask if they can enter.

4. Prepare an observation sheet/scheme. For many research topics, you will be able to outline initially which elements will be relevant to you in the context of later analysis. Develop a table with a list of these elements. You will fill in the table with your observations during the visit.

Tools

During the study, you will collect a lot of information of a different nature: words, sounds, photos, and sketches. Don’t forget to prepare those that are most relevant to the study site:

- Pens and notepad

- A printed observation sheet

- Smartphone to take photos and videos

- Dictaphone

- Small camera

- Laptop

Remember that a laptop will not always be the best option! In the case of field research, you will be moving around a lot or talking to the respondent in a busy outlet where there is simply no way to open a laptop. A simple notebook will work well in these situations. A large and highly visible camera, even if you only take pictures of objects around you, may intimidate your interviewees. If you want your presence to be unobtrusive, it is better to take photos with a smartphone.

Necessary details

Remember that you will not be conducting every study in one location, and you will encounter projects that will require the researcher to be shadowing in the field stretched over many hours.

When conducting the extensive digital workplace research at the global FMCG corporation I mentioned earlier, we focused not only on office workers but also on sales representatives working in the field. The researchers travelled with the sales representatives from point of sale to point of sale. Throughout the day, they looked at how the representatives use the digital tools given to them by their employer and to what extent these tools fit into the context, reality, and working environment.

Another research adventure awaited us on a project for a large logistics company. The researchers accompanied the couriers at work and observed to what extent the mobile tools supported their tasks. The researcher’s working day started at dawn on a frosty day at a distribution centre and included accompanying couriers to operate parcel machines, among other things. At the same time, at other points in the city, the researchers observed customer behaviour under the parcel machines and conducted short interviews.

So if you know you will be on the move all the time, don’t forget to take care of the details: comfortable shoes or a bottle of mineral water. These are really important!

Fieldwork – a key stage of ethnographic research

A few rules to get you started

The day of the survey has arrived? No worries, it’s sure to be an interesting research adventure! During fieldwork, remember these few rules:

- Give yourself and the respondent time. Introduce yourself, say hello to the people working at the location, and briefly tell them what you do.

- Start with simple questions. Ask the respondent to show you around the workplace, show you where his/her position is and what it looks like. Ask what his/her typical working day looks like.

- If you are in this type of place for the first time in your life, e.g. an installation control room in a production plant, don’t be afraid to ask questions that will seem obvious to your respondent. This way, you get to know the context and the respondent will feel more confident because they are navigating an area they are familiar with.

- Observe, don’t judge. Don’t fall into the trap of your own beliefs, try not to assign meanings to the objects and situations you see just yet. First, open your eyes and ears to what meanings the users themselves give them.

- During the interview, ask as many open-ended questions as possible, and do not direct the user’s attention immediately to the detailed threads you have indicated. Find out what threads the respondent will bring up on their own initiative.

- Look at the context in which the system is used. You are not only interested in the computer and its screen, but also in what is around you.

- If you see something you don’t understand, take a picture and ask your interviewee later.

- Keep your eyes open, but always keep the main purpose of the study in mind.

What to observe?

Keep an eye on these elements:

- Behaviour. What do people do and how do they do it?

- Artefacts. Objects around that may have meaning.

- Devices. The whole ecosystem of devices, not just computers, but tablets, warehouse or shop collectors, code scanners, and the relationship between these devices and the system you are analysing

- Tools. How and for what do people use the tools at their disposal?

- Language. What and how do people speak: what terms do they use, is the language formal or the opposite, do they use jargon?

- Relationships. What relationship do people enter into with other people or objects?

- Context. Sounds, light, weather, the rhythm of the day, the pace of work, other people

- Location. People’s relationship with the place

- Emotional reactions. Towards tasks, situations, other people’s actions

- Patterns. Any patterns, structures, repetitive actions, and phenomena

- Start by organising your material. Arrange your notes and any diagrams or sketches you have drawn. If you missed it earlier, describe exactly which location they relate to.

- Carefully describe and archive the photographic material. What is in the photo may be understandable to you because you were/are in that context. Another person may interpret the photographed reality differently. Descriptions are key, especially if the study was carried out by a team of several researchers.

- Write down your initial conclusions, any that come to mind after the research, even before the detailed analysis.

- Organise a briefing of the researchers. If you worked as a team, you need to meet and exchange key observations. Discuss the similarities and differences you observed in the different sites. Get organised. Agree on a common way to analyse: grouping and tagging information, working tools, and sharing files.

- Go into detailed analysis. Organise, collate, and group information. Focus on elements you observed (e.g. behaviours, artefacts, language). Compare in subgroups and across locations. Consider if and what factors influence a given state of affairs and if we as designers can influence them.

- The interpretation of the collected material, both the user’s and your interpretation as a researcher, is very important. Remember to also be vigilant when analysing, just as you did when observing. Do not project your own beliefs or perceptions onto your subjects, if you are carrying out research on another continent or in another country, and do not assess the behaviour observed in the group under study through the prism of your own cultural realities.

- Turn observations into recommendations. If your analysis indicates that there are gaps in the system being analysed, indicate to the designers which ones and suggest how to fill them through proper design. If you discover areas with potential for improvement – consider how they can be improved through design. If you discover a previously undiagnosed need – consider whether it can be addressed digitally and, if so, what conditions would need to be met by system functionality that responds to it.

So much for the practice of contemporary ethnographic research and the application of cultural anthropology traditions to user-centred design and as an input to the design process! But what if we look to the future?

Will artificial intelligence one day replace ethnographic research?

As technology develops, we are also gaining new tools in the areas of design thinking, user experience, and social or marketing research. Can AI support and eventually replace ethnographic research?

Let’s let our imagination run wild! “AI will always be objective, and we researchers are only human!” “AI will unequivocally determine whether a user is experiencing frustration while using the system, it will unequivocally answer whether a mobile device speeds up or slows down a task and by how many minutes.” “It will collect data consistently across locations, so they will always be compared with each other!” “On top of that, AI will not superimpose its cultural interpretation on the data because it is completely culturally independent!”. In the first instance, these types of arguments will probably come to mind. A tempting vision? In my opinion, not at all!

While advanced research on the recognition of emotions and the interpretation of facial expressions by artificial intelligence is constantly being conducted, empathy, the ability to “step into the shoes” of another human being, sensitivity, the ability to observe context, and an eye for detail, and the ability to gain the trust of a respondent is a range of social competences inherent to humans. It does not appear that artificial intelligence will be able to surpass humans in these in the foreseeable future – fortunately!